How to rebuild a city with Karam Alkatlabe

An excerpt from the new The Wolfson Review

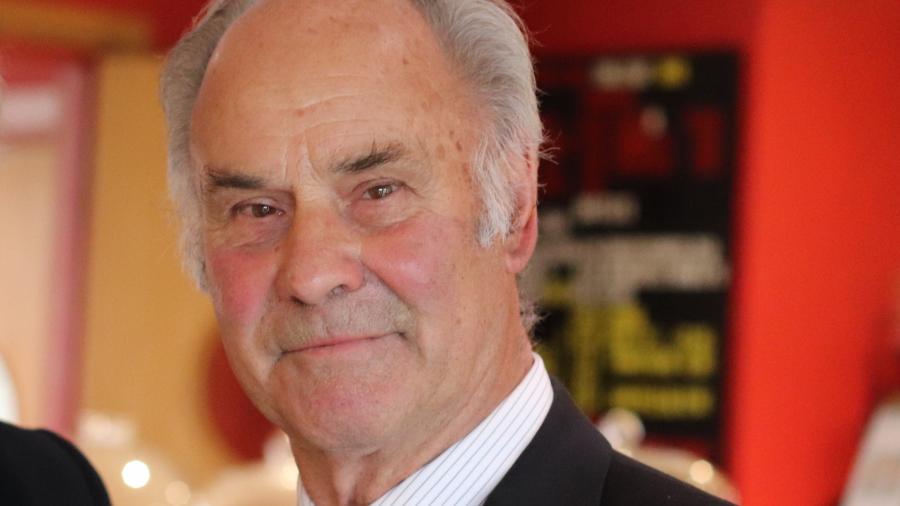

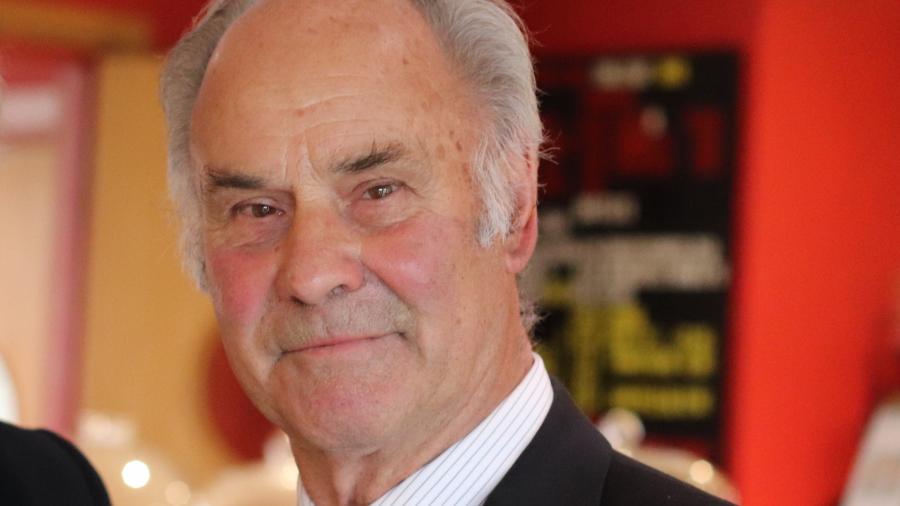

Half a century after he studied at Wolfson, John Hughes (Civil Engineering, 1969) is back at the College.

Relaxing in the Club Room, it’s barely ten minutes before he finds himself in spontaneous conversation about rowing with third year English student, Liam Tayler.

“I’ve been meaning to get into it,” says Liam, “but I’m a bit hesitant. It’s quite a commitment.” “You should do it,” says John, instantly, “the comradery you’ll develop is wonderful: and that makes such a difference to your experience.”

John certainly found comradery in sport when he was at Wolfson – and there’s proof a few metres away from where he’s sitting: his name is on the commemorative oar hanging above the College bar, alongside his fellow crew from 1970.

“Rowing really helped me find my place at Cambridge. I played on the College squash team too – and that introduced me to two different groups of people. Through sport, I had a wonderful introduction to College life.”

John is not back just to talk about rowing, however, but to sign off a significant donation to the College – supplemented by a University donation – that will create a new PhD scholarship at Wolfson, The John Hughes PhD Studentship: Wolfson’s first fully endowed PhD studentship.

John’s donation will leave a significant legacy at Wolfson – and he has left no small impact with his own research and invention since arriving at Wolfson all those years ago. John was the first at Cambridge University to conduct research on the pressuremeter, an instrument for measuring the strength and stiffness of soil and rock.

Today, pressuremeters are used widely in geotechnical engineering, on land and water, whether it’s building onshore and offshore wind energy, bridge construction, tunnelling, rail and highway infrastructure, and port and harbour development. Many of them use the version developed by John himself.

“The first pressuremeter was developed in the U.S. in 1953, but it had limited capabilities,” says John. “My approach was to change the original design to include accurate measurements of the strain and pressure by using modern electronics and mathematics to develop more accurate analysis of soil properties.”

Born in Auckland, New Zealand, John’s academic journey was sparked by an experience as a young engineer in Canada. He was working on a new railway line, building what they thought was the last landfill in a series of embankments. They were just about to finish, and had left the site for a celebratory meal, when the fill collapsed.

“The question was, why had it collapsed? What kind of pressure had caused it?” he says. Shortly after, he began to think about how it was possible to accurately measure the stress within the soil, so as to better inform projects such as tunnel building and general construction.

“There had to be a mathematical answer to the problem,” he says. “I came to Wolfson to find the solution to a problem – to find an equation basically.

“My supervisor seemed to be keen on what I was trying to do. Most students at that time didn’t come with a specific problem they wanted to solve – but I did. And Cambridge had the equipment to help me solve it.”

And solve it he did.

“Essentially, I built a miniature boring machine, and instead of building it to work horizontally, I built it to work vertically, to measure the stresses in the ground.”

Eventually, a Cambridge company – now Cambridge Insitu – visited the lab and saw the great potential in John’s prototype, turning the idea into a modern machine.

“I was most interested in fixing the problem and handing it on,” says John. “I’ve seen what the company has done all over the world. And I’ve done the same thing with my own companies, with the same technology – though I’m not nearly as good at making it as them. They improved it immensely, so it’s really owing to them that it got to where it is now.”

Indeed, John’s basic idea is now – fifty years later – still being used by Cambridge Insitu, and by companies all over the world, on projects from the Second Severn Crossing, the HS2 in the UK, and the Jubilee underground extension in the UK, to the Bangkok wastewater outfall tunnel in Thailand and the Canadian Site C Clean Energy hydropower project.

“It’s pleasing that the same technology is still being used today,” he says. “Not many technologies largely stay the same over fifty years. It’s still answering the question I tried to answer half a century ago.” After running pressuremeter companies in Canada and the U.S., John is now retired, but this year he is publishing a book about his life’s work. “The now-manager of Cambridge Insitu said that we should put something together about our lives in the business,” he says. “I had never thought about that, but thought that was a good idea. So that’s what we’re doing now – putting a hundred years of experience into one book.”

The book reflects a clear strain that runs throughout John’s life: it’s about passing on knowledge, passing on benefits from one generation to the next. His new book, The John Hughes PhD Scholarship, and his legacy in ground engineering are all testament to that noble ambition.

This article is an excerpt from the new edition of The Wolfson Review, the College magazine. For the full article, and for more stories from the College, check out The Wolfson Review online.

A load cell pressuremeter

John Hughes's name on the oar above the College bar

John Hughes, with Wolfson President, Professor Jane Clarke, signing his donation to the College