How to rebuild a city with Karam Alkatlabe

Karen Spärck Jones is now frequently referred to as the woman who laid the foundation for the internet search engine – but as the technological landscape develops, we can see the relevance of her work in much more of the modern world, including artificial intelligence and chatbots.

Join us to explore the many volumes collected by Karen Spärck Jones, the scientist often known as the woman who laid the foundation for the internet search engine.

Book onto the tour:

11.00 - 12.00 on Monday 11 September

14.00 - 15.00 on Monday 11 September

Meeting Place: Porters Lodge

Karen’s contributions to computational linguistics (CL) and information retrieval (IR) were groundbreaking, and her invention in 1972 of the concept of ‘inverse document frequency’ (IDF) is considered the basis for how the modern internet search engine works.

However, Professor Ann Copestake, Head of Department of Computer Science & Technology and Professor of Computational Linguistics, and a Wolfson Fellow, believes we can look at Karen’s work through the lens of even more recent technological developments.

"She was one of the first people, possibly the first person, to do practical experiments investigating the idea that computers can obtain clues about meaning from the textual context of words,” says Professor Copestake. “This idea is key to much of modern AI, including systems such as ChatGPT."

Professor Copestake points to Karen’s early work, including her 1964 PhD thesis, as carrying the principles of the AI we we’re witnessing today, as well as to slightly later work which demonstrated perhaps the first work in which a mathematically plausible approach to calculating distributional similarly between words extracted from ordinary text.

Similarly, John Tait, formerly of the University of Sunderland, and a long-time friend of Karen’s, also highlighted the importance of Karen’s early work in his obituary for Karen in 2007:

“In the long term perhaps her greatest contribution will come to be seen to be her PhD thesis (1964), which was far ahead of its time,” he wrote. “It brought together statistical or machine learning approaches with the use of an existing resource (Roget’s Thesaurus—punched onto cards!) and still can be read with profit today. It can be viewed as the forerunner of a whole range of more recent attempts to derive semantic information on an empirical basis.”

Born in Huddersfield in 1935, Karen initially read History at Cambridge, before graduating in Philosophy. In 1957, she was to join the Cambridge Language Research Unit, working closely with Margaret Masterman, who was herself a student of Wittgenstein – and it was here where we can see the seeds of her astonishing innovations.

While recognition for her work was to come late, she was awarded numerous awards during her career, including Fellowships of the American and European Artificial Intelligence societies, Fellowship of the British Academy, the ACL Lifetime Achievement Award, and the Lovelace Medal of the British Computer Society.

Karen was a member of the Cambridge University Computer Laboratory for most of her working life, and she was awarded a Readership in 1994 and a personal chair in 1999.

Collaboration was key to Karen’s success, too, and one collaborator was perhaps more important than most: fellow computer scientist, Roger Needham, whom she married in 1958. The pair collaborated on numerous projects, including the automatic construction of thesauri – in order to find out if a computer could understand words with many meanings.

Like Roger, Karen was made a Fellow (2000) and then Honorary Fellow (2002) of Wolfson College, part of a rich tradition of scientists – female scientists in particular – at the college, which also includes Dr Norma Emerton and the current President, Professor Jane Clarke.

Both Roger and Karen have rooms named after them at Wolfson, so their names are spoken most days by students in College even now.

Wolfson College President, Professor Jane Clarke, the first woman and the first scientist to serve as President of the College, approaches Karen’s legacy from her own unique perspective:

“We can look at Karen’s work very much as a quest for communication, for meaningful information, and for meaning. That’s a very powerful legacy to leave – and the fingerprints of her thinking and her innovation are all around us in our technological world,” says Jane.

“Her legacy is here at Wolfson College too. She was an inspiration to women in her field, to women in science more broadly, and she was a big part of the long line of women scientists at Wolfson of which I feel privileged to be a part.”

Indeed, Karen’s encouragement and inspiration to other women in computing – and science more generally – is a vital part of her contribution.

“She was a powerful advocate for women in computing and served as a role model for many young women coming into a subject dominated by men,” said Haroon Ahmed in his excellent book, Cambridge Computing: The First 75 Years.

It’s a point made strongly by John Tait too: “Although Karen felt she was never overtly discriminated against as a woman, it must have taken considerable courage and tenacity to develop a leading academic career at a time when society’s expectations of women went little beyond their roles as wives and mothers,” he says.

“She noted that in professional circles she was very frequently the only woman, and made very active efforts, especially in recent years, to interest young women and girls in careers in computing, believing that “computing was too important to be left to men””.

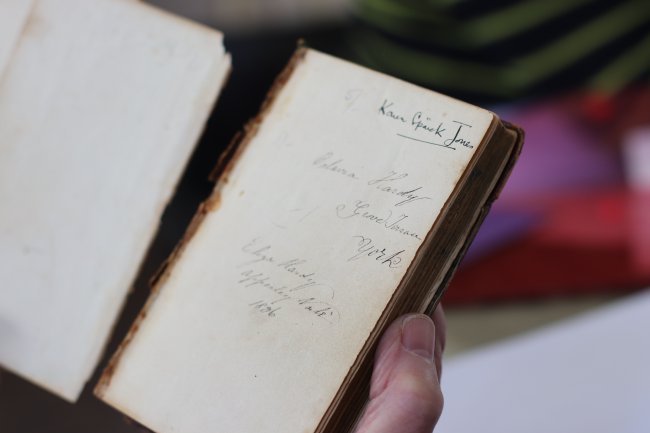

One project at Wolfson has recently brought one of Karen’s other legacies to life: her books. Wolfson members will be familiar with books that line Karen Spärck Jones Room. This collection comprises around 2000 modern books that illuminate Karen’s eclectic interests, including art history, handicrafts and textiles, geography, politics, architecture and music.

Less well-known is that she donated a further collection of 200 rare books, printed prior to 1900, which are stored in the Library basement. However, the books were unlisted and so could not be found by librarians nor researchers.

In August 2022, 5 volunteers from the Arts Society Cantab started work at Wolfson Library cleaning the books, tying up loose boards, listing and, most importantly, giving every book a shelfmark so that we can find it again.

“These books reflect the myriad of influences on the mind of Karen Spärck Jones,” said Wolfson Librarian, Laura Jeffrey. “The volunteers completed the project in February this year and now that the books are listed, we can work to make them accessible to a new generation of researchers via the Library catalogue.”

The books are equally varied spanning Classics (the oldest book in the collection is a 1562 edition of Epistulae ad Familiares by Cicero), literature, history, geology, botany, and even the art of cookery (dating from 1747).

Wendy Walford, one of the volunteers, said: “Students and staff were consistently friendly and interested in what we were doing. And there were occasional excitements to be found amongst the collection. Rewarding gems like the book published in London in 1665 which, when opened, exhaled smoke fumes. And then there was the rather gruesome tome which described a father’s dissection of his own son - with graphic illustrations!”

The neurobiologist fighting Parkinson's through research

Find out about the Wolfson-CDT PhD Studentship for Women in Physical Sciences.

Arts Society volunteers clean, classify and sort books from Karen Spärck Jones' collection

Karen's signature adorns many of the books in the collection