New Press Fellows arrive at Wolfson

In an interview from the upcoming edition of The Wolfson Review, one of the world’s leading historians, Professor Wang Gungwu AO CBE, looks back on a unique opportunity to build a nation - and the mystery of falling in love.

When Honorary Fellow Professor Wang Gungwu picked up the distinguished Tang Prize in Sinology last year, he was described as “one of the most original and inspiring historians of our times”.

One of only ten people given an honorary degree by the late Duke of Edinburgh at the University’s 800th Anniversary Honorary Degree Congregation in 2009, he has been a leading historian on Sino-Southeast relations for decades.

His unique approach of understanding China through its complex relationship with its southern neighbours has produced classic monographs and significantly enhanced our understanding of China and the Chinese people’s place in the world.

He grappled with the concept of globalisation before the term had even been coined, and indeed he coined many now-canonical terms to enable a more precise understanding of the Chinese experience.

In particular, he adopted the term ‘Chinese overseas’ to replace politicised terms such diaspora and huaqiao, and developed categories of migration through careful historical analysis that have allowed historians to understand the complex reality of the migrant experience.

This year, Professor Wang published the second volume of his memoirs. However, as someone with such a clear-eyed view of terminology, he balks at the prospect of using the term 'memoir': “I may have sounded as if I was going to write my memoirs. If I gave that impression, that was a mistake. I am still not sure I want to write one.”

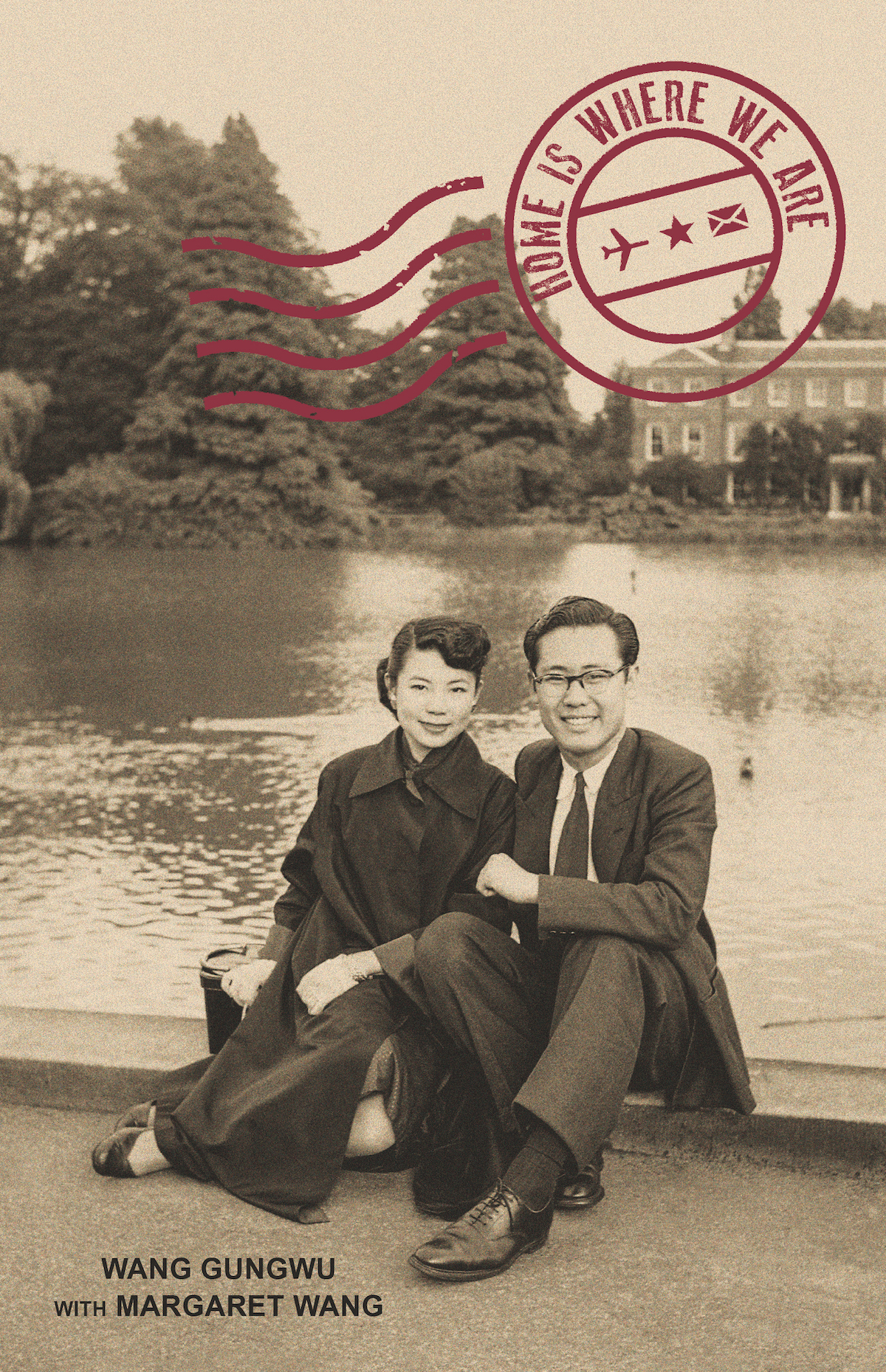

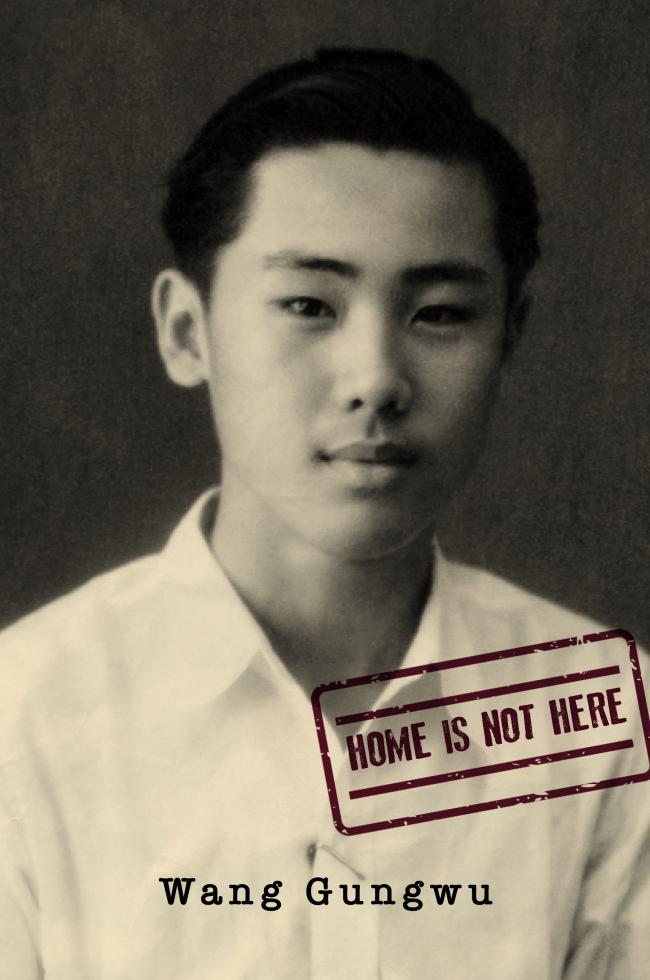

Both books are nonetheless wonderful and revealing personal histories. Home is Not Here (2018) chronicles his childhood and early adulthood in South East Asia and China. The follow-up, Home is Where We Are (2021), traces his return to Malaya, his meeting of his wife and their marriage against the backdrop of emerging nation-building in Malaya.

Both volumes take a dialogical approach to personal history. The first beautifully interweaves parts of his mother’s autobiography, while the second was co-written with his late wife, Margaret. These intertextual dialogues work brilliantly to bring the personal and the collective histories alive, but were in fact a happy accident.

“What I did was unplanned,” he says. “I was lucky that both had their writings at hand. My mother wrote her story and gave it to me before she passed away. It was so well done that I translated it for my children. When I was persuaded to write my own story for them, I thought it would come more alive if I included what my mother recalled.”

Professor Wang was born in Indonesia to Chinese parents who had always intended to return home. “It didn’t work out,” he says, and it’s perhaps no surprise that this grappling with the realities of the experience of Chinese overseas, their complex and conflicting identities, and the looming question of where is home have been recurring concepts throughout his writing. Both volumes of his personal history reflect on these themes in ways that are both historical and intimate.

“My family inspired me to think hard about what is home,” he says. “Both families started as sojourners who turned immigrants and eventually settled in lands that were very foreign. The two volumes sought answers to the question of where was home. I think my wife and I found our answer and our children now understand how that happened. That made the ending a happy one.”

Home is Where We Are recalls a time when Singapore and Malaysia were on the verge of independence, and of a young generation eager to seize the future, convinced they were in the right place at the right time to shape a nation. Professor Wang was at the heart of these efforts, and he is unflinching in his assessment.

“I was excited by the idea of building a nation but too naive to understand how difficult that was to be,” he says. “Malaya was exceptionally difficult because of its unique mix of peoples, the Chinese-led MCP in revolt accompanied by the communist victory in China, and the fragmented colonial heritage.

“The British had left several similar messes elsewhere, leaving diverse peoples within borders that were artificially created. What became Malaysia was one of the worst examples and it simply did not have the basic conditions for successful nation-building. Singapore was lucky to have separated. It did much better by concentrating on becoming an open global city-state and not pretending it could become a nation.”

Against this backdrop of difficult nation building, the book traces the relationship between Professor Wang and his wife, Margaret. Their relationship grew out of a quest to grow into the country that was emerging around them.

“I came to realise that I was encountering something called love that I had not given much thought to in the past,” he writes. “Meeting Margaret led me to learn that the word could describe what I felt. How that happened was and still is a mystery.”

Their writings circle and answer each other throughout the book. “By 2018, Margaret was unwell,” Professor Wang explains sadly, “and I wanted to tell our story of how we met and what a difference that made to my life, with her agreement and the children’s, parts of her story were woven into mine.”

Unfortunately, Margaret passed away on 7 August 2020. “While she saw the whole manuscript and agreed to the inclusions before the final version went to the publishers, I was very sorry she did not live long enough to see the published book.”

A clear ambition of both works is to provide a personal testimony on the past. In the introduction to Home is Not Here, Professor Wang writes that, “while we talk grandly of the importance of history, we are insensitive to what people felt and thought who lived through any period of past time.”

Nonetheless, it took some encouragement before Professor Wang finally agreed to write his own version of that period in history.

“My Heritage Society friends convinced me that more people should be encouraged to write their stories — perhaps for the family and not necessarily for publication, but they should make sure to have them preserved in some form. My only regret is that others haven’t tried to write their stories, in the way that I have told mine.”

In the end, it was Margaret who led the way for volume two. “She had regretted the fact that her mother, a remarkable woman, had not written her story. She was especially sorry she did not ask her questions about her life while her mother was alive. So she set out to write her story for our children. The children so liked it that they turned to me and asked me to do the same. After being reminded for several years, I agreed to write about my childhood for them.”

Professor Wang's experiences in Cambridge are certainly less complicated, and he speaks fondly of receiving his honorary degree from the late Duke of Edinburgh at the 800th Anniversary Honorary Degree Congregation.

“That was a great honour,” he says. “One of the greatest gifts to humankind is the idea of a university and Cambridge is one of the finest examples of what is possible when the ideals of dedicated scholarship and academic freedom are protected from politicisation and irrational nationalism.”

As a Wolfson Honorary Fellow, with a student award - the Teo Wang Gungwu Award - named in his honour, and numerous College visits under his belt, his connection to Wolfson is strong, too.

“I have enjoyed all my visits to Wolfson College,” he says. “Under good leadership, the College has maintained the high standards that made Cambridge one of the most respected universities in the world.”

Now in his tenth decade, Professor Wang looks back critically but fondly on the past, and with a sense of deep authority. He is less certain about the future, however, and what might happen in the next 90 years.

“Much will depend on the countries or peoples who have the power to provide global leadership,” he says. “If they concentrate on dominance and holding hegemonic power, and not on accepting differences and trying to work together, there is very little hope of a good world. I am not sure how far we can get that right in 90 years.”

This article features in this year's The Wolfson Review magazine, which will be launched digitally this year.

You can purchase both Home Is Not Here and Home Is Where We Are on the NUS Press website (Singapore/SEA), the University of Chicago Press website (North America), website (UK/EMEA), Eurospan (UK/EMEA), or through your local bookseller.

Professor Wang Gungwu and his wife Margaret at Kew Gardens

Home Is Not Here, his first memoir, was released in 2018.